This legal case study deals with a client who switched his life insurance cover from one company to another, on the advice of his adviser. He was left uninsured when the new insurer voided the contract due to non-disclosure issues. The court concluded that the adviser was negligent and engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, in that he was too hasty and failed to sufficiently impress upon the client the risk he took replacing one policy for another. BT’s Senior Product Technical Manager, Katherine Ashby, examines the case and identifies the key learnings for advisers.

[hr]

At a Glance

Submitted by: Katherine Ashby

Role: Senior Product Technical Manager, BT Life Insurance

Topics covered: insurance replacement advice

[hr]

In Detail

Background

Over the summer break we saw the conclusion of a controversial long running court case involving one of the big four banks and insurance replacement advice.

The case quickly became referred to as ‘the churn case’, as many lawyers and industry commentators linked the case with inappropriate advice practices and churn concerns recently highlighted by ASIC.

For advisers, perhaps this case could be more accurately described as an ‘advice process case’ – as although the facts presented themselves as a case about responsibility for non-disclosure, at the core of the case was the underlying issue of whether the advice given was adequate and appropriate in the first place.

On the surface, the product advice doesn’t raise too many alarm bells, but throughout the court proceedings it became apparent that the adviser failed to properly discharge his responsibilities when providing written advice to cancel one policy and replace it with another – and that’s where the problems arose.

Case study facts

The client went to see the adviser in September 2010, where the adviser found the client did not have any assets, meaning the only advice opportunity available to him was a review of the client’s existing life cover policy. The policy had been in force since 2003.

The adviser recommended the policy be cancelled and replaced with a policy issued by the same institution for which he was employed.

Policies

The Statement of Advice (SOA) listed the standard risks to the client, which included the following:

- Do not cancel your existing policy until the new one is in place

- The insurer may not pay a benefit if you do not comply with your duty of disclosure

- You will be required to provide health and financial details and the law requires you to disclose all the information you know that is relevant

- If you do not, the insurer may void your cover or prejudice any claim.

Neither the adviser nor client knew about the three-year period set out in the Insurance Contracts Act s29(3), which allows insurers to void contracts that they would not have entered into had a misrepresentation not been made. As such, the adviser did not warn the client of this.

The client accepted the recommendation and the application was completed electronically via the e-application. The adviser completed the application, and stated that he verbally asked the client every question on the application, however, the client maintains he was not asked any questions about his health. All health questions on the application were answered ‘no’. In addition, the fact-find listed the client’s health as ‘excellent’.

What happened next?

One year later, the client was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and two months later he was classed as terminal. He then made a claim and the insurer avoided the policy claiming non-disclosure. Among other issues, the client’s recent medical history showed the following:

- Reflux

- Raised LFTs

- Heavy drinking (approximately 8-10 heavy beers per day, as opposed to the 8-10 standard drinks per week, as indicated on the application)

- Heavy smoking for over 10 years, however, the client appeared to have ceased smoking 12 months prior to his the application

- Referral to a specialist, which the client had not followed through with

Court proceedings

The client first sued the insurer, however, was unsuccessful. It is clear from his recent medical history that had the above medical issues been disclosed by the client, the insurer would not have offered cover.

Following the initial ruling, he then successfully went on to sue the advice provider. As a result, the advice provider was forced to pay the client’s life cover sum insured as well as additional costs.

Finally, the case went to appeal in December 2013, and the judgement against the advice provider was upheld.

Reasons for the judgement

The client was successful as the court found the adviser gave written advice that was misleading and deceptive. The judgment highlighted three key areas:

- Failure to advise the effect of the Insurance Contracts Review Act 1984 (Cth), s 29(3)

- Insufficient information at the time of advice to allow a proper comparison

- Inability to recommend a competitor’s products.

Insurance Contracts Review Act

Neither the adviser nor client knew about the three-year period set out in the Insurance Contracts (IC) Act s 29(3), which allows insurers to void contracts they would not have entered into had a misrepresentation not been made. As such, the adviser did not warn the client of this, verbally or in writing.

The IC Act sets out the remedies available to insurers if a client has not disclosed all relevant information. In the first three years of the contract, a policy can be voided if the insurer can show it would not have offered cover had the client fully disclosed all relevant information.

The non-disclosed issue does not have to be the reason for the claim – it just needs to be a reason the insurer would not have offered cover. After three years, s 29(3) does not apply and an insurer needs to prove that the non-disclosure was fraudulent or the misrepresentation was made fraudulently (s 29(2)).

As the client’s existing policy had been in force for many years, he was well beyond the three-year period. The judgment stated:

“Although the SOA did disclose the risk of avoidance for non-disclosure, it failed to disclose the important effect of s 29(3)… s 29(3) was, in the adviser’s words, “news to me”.

…In circumstances where in truth there was very little material difference in the policies, that statutory difference was very material to the decision Mr Stevens was being asked to make. It was misleading and deceptive to advise him to do so without drawing it to his attention.”

Hence the court found that the impact of this legislation was actually the biggest material difference between the policies, and should have been disclosed as a lost benefit in the policy comparison.

Proper comparison

The comparison between the new and old policies was incomplete. Along with the failure to disclose the impact of the IC Act above, both a premium and benefit comparison was criticised.

The SOA provided the reason for the replacement advice as “existing life insurance more expensive dollar for dollar and no trauma insurance within the existing policy”. The court found this statement could not be made, as the adviser was not in a position to know if the new insurer would accept the client and if so on what terms. There needed to be some qualifications made around that statement, so that it was clear it only applied if the client was accepted at standard rates.

The adviser’s comparison of premiums was confined to the first year

The court was also very critical of the adviser’s premium comparison:

“The adviser’s comparison of premiums was confined to the first year. But he was attempting to sell a product designed to last a lifetime. It was misleading to confine his comparison to first year’s premiums. Further, it would be necessary to take into account the facts that (a) the benefit payable under the existing policy increased (subject to a direction to the contrary) by 3% per year and (b) the structure of the premiums (stepped or level) under the existing policy. There is nothing to suggest that the adviser even made an inquiry as to that structure.”

Finally, the adviser did not make any policy comparison at benefit level. He admitted in court that he had not researched the existing policy, nor sourced a copy of the policy document. Although the policies were in essence, quite similar, the adviser still had an obligation to do so.

Inability to recommend a competitor’s product

This last point is interesting and perhaps raises the most questions. The adviser asserted in court that he was not permitted to recommend the competitor product, nor recommend the client maintain his existing cover.

The court used this statement, and the alternative strategies from the SOA to make this point. The SOA listed two alternative strategies:

- Self insure – insufficient capital/equity to self insure

- Full insurance review – client declined.

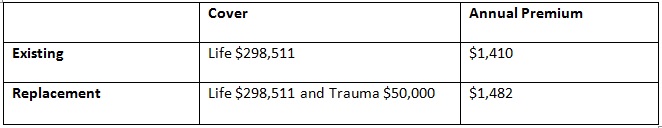

The judgment was very critical and refers to these alternatives as “absurd”. It questions why the most obvious alternative – to just replace the life cover and have a lower premium (of $1,097) – or otherwise, to maintain the existing policy, were not considered. The conclusion was made regarding the latter that this was because it was not allowed by the licensee.

This point is jarring as it is common to recommend that cover be left in force, even though that product is not on the Approved Product List (for example, employer or industry super fund cover). Hence we would question whether this was the actual advice process, or whether it was simply the impression the adviser was left with by his superiors.

Other facts of the case

The use of para-planning was continually criticised and was not helped by the fact that the SOA had only one sentence of personalised advice and many errors.

there were no diary/file notes, which meant that the adviser had no evidence to prove his version of events

Worse still, there were no diary/file notes, which meant that the adviser had no evidence to prove his version of events. All aspects of the case, such as what was said, whether the SOA was presented and whether any verbal warnings were given, effectively came down to his word against the client.

It was noted that the adviser had to carry out this process hundreds of times a year, as opposed to the client, who had only done it once. Hence without supporting evidence, it seemed that the court would be more likely to take the word of the client.

Finally, even though it was not central to the case, without diary notes or any documentation, the adviser could not prove who completed the application. Proof could have been supplied if the adviser had asked the client sign a copy, provided a copy to the client or, of course, supplied diary notes. Any record of conversations that took place during the appointment would have added depth to the interactions and shown corroboration.

Key facts to take out

- Written advice to replace a policy based on premiums needs to include reference to any conditions on which the advice rests – for example, acceptance at standard rates. Further, it must include reference to the structure, stepped or level, and consideration beyond the first year.

- If replacing a policy that is more than three years old, the effects of the Insurance Contracts Act s 29(3) should be outlined as a lost benefit.

- When stating an alternative strategy, advisers will need to be careful to ensure that if more feasible strategies are available, then those should be outlined, rather than the generic alternate strategy, “self-insure”.

- Consider methods to ensure that you can prove the client was asked the application questions, whether that be through:

- Using an insurer that provides a copy of the application to the client

- Documenting conversations that took place during the application in a file note

- Simply printing a copy of the application and asking the client to acknowledge that all answers are correct.

- As always, never offer advice that won’t be of benefit to the client.

On the surface of this case, when comparing the two policies, it appeared that there was every reason to recommend a replacement. However, the case ultimately came down to whether the advice was misleading or deceptive, and whether the advice was appropriate given what the planner ought to have known.

Ultimately, regardless of who completed the application, who was responsible for the non-disclosure, or that the evidence supplied by the client was at times referred to as “unreliable” – as the adviser had not fulfilled the necessary requirements for replacement insurance advice, the client had grounds to successfully win the case.

For further assistance please contact your BT Life Insurance BDM or lifetechnical@btfinancialgroup.com

To view a copy of the case notes, click here.